Bad news: measuring engineering productivity is doomed

Good news: there are effective ways to address the needs of all involved—engineers, managers, executives, & customers

The desire to measure engineering productivity expresses a genuine human need. The problem is that trying to meet that need through metrics or even surveys inevitably poisons the data on which productivity measurement relies. Let’s dive into the structure of this dilemma before talking about the actual needs & how they can actually be addressed.

Tradeoffs

Paying subscribers to Tidy First? receive weekly Thinkies, habits of creative thought I’ve collected. Lately I’ve been particularly interested in thinking in terms of tradeoffs. Tradeoffs have a surprisingly subtle structure, leading me to write a booklet diving into the details (also available to paying subscribers).

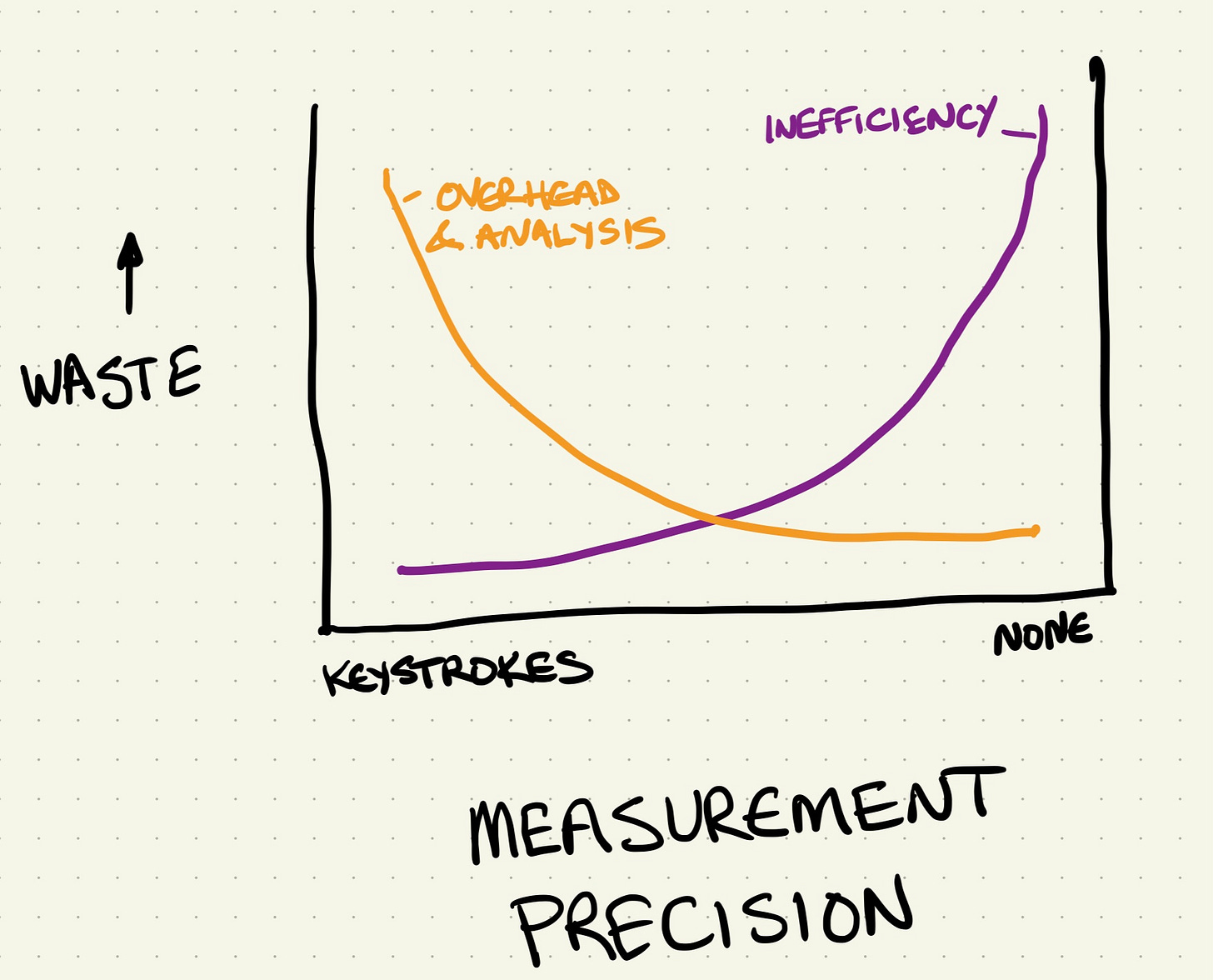

Measuring engineering productivity is an excellent example of a tradeoff. It has all the anatomical elements of a tradeoff:

A goal to be improved upon—reducing wasted effort.

A continuum of possibilities for addressing the goal—measurement from none to surveys to increasingly detailed metrics.

A response curve—how much waste you expect to eliminate for each of interventions.

A counter response curve—waste created because you went too far

Graphically, it can be rendered like this:

Seems sensible—diminishing marginal returns & increasing overhead for greater measurement precision. Sensible but wildly wrong.

Better Picture

The response curves:

Are the wrong shape.

Are out of proportion.

The counter-response curve in particular misses gigantic effects.

The potential gains from productivity improvement aren’t infinite. You have an organization now. You have customers now. You’re doing something. It works. Some.

If you kept improving for years, yes you might make dramatic improvements, but that will come through all kinds of interventions, not just measuring productivity. Measuring & responding may net a win but then the bottleneck will move elsewhere.

Overhead & analysis remain. Who knows their magnitude compared to the potential efficiency gains. I’ll just make them similar. Draw your own curves for your own tradeoff.

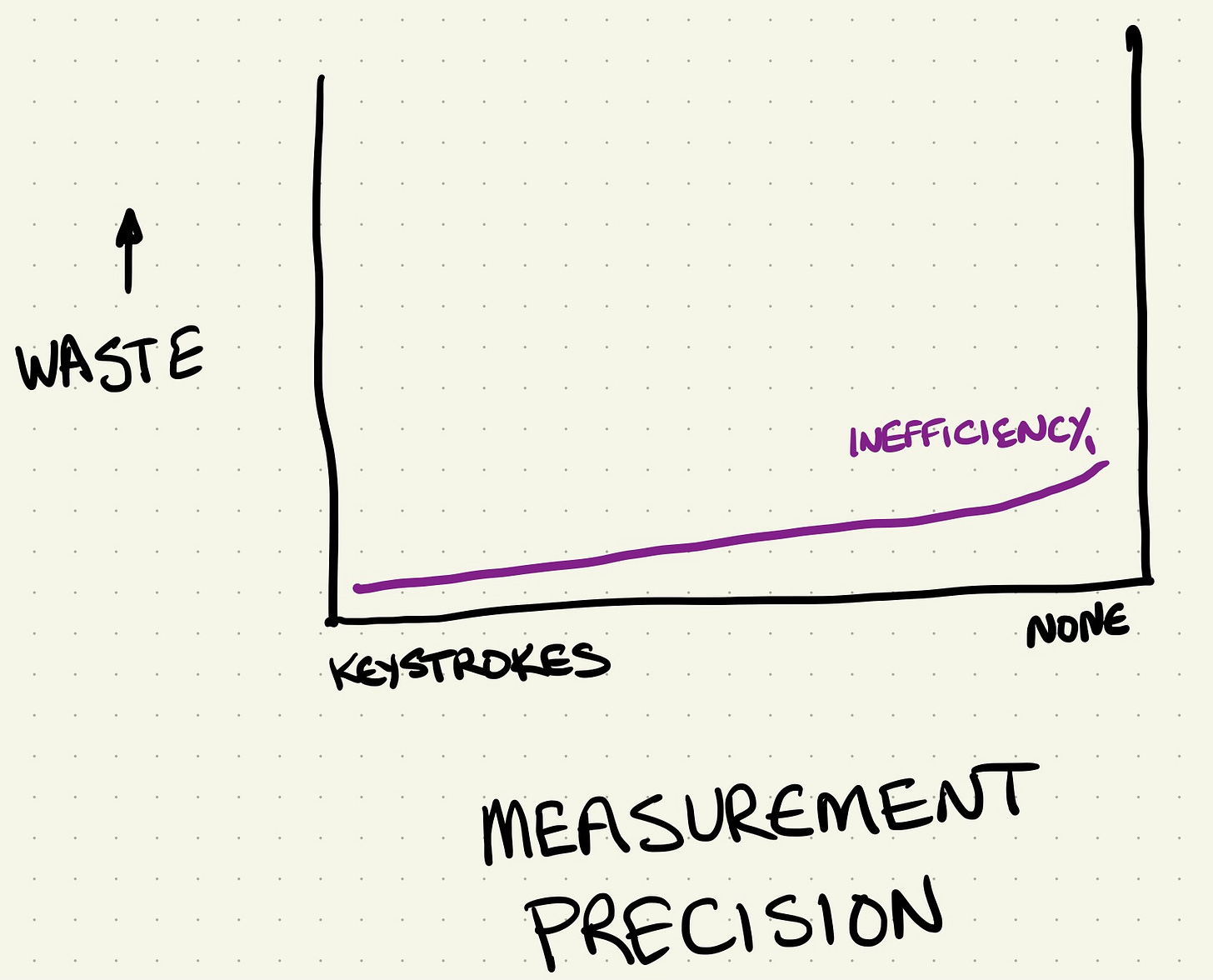

As soon as metrics have consequences, gaming begins. Goodhart’s Law kicks in1. The cost rises as people spend effort gaming the system instead of doing useful work. Also, the distortion of the measurement reduces any value to be derived.

Note that it’s hard to catch gaming, exactly because it’s intended to be invisible to operation of the metrics. How much effort do you want to expand catching cheaters instead of setting up a system where cheating doesn’t make sense?

Precise measurement rises further. As departments’ incentives diverge, the incentive to collaborate diminishes. Why would I make you look good if that’s going to make me look worse by comparison? Work that would have been done together for mutual benefit ceases.

Again, these costs are completely off the books, unaccounted for. Engineering just seems slow. I know! Moar mezzures!

Alternative

The most surprising lesson for me about the whole “measuring engineering productivity” conversation has been trying to get a straight answer to the question of, “Why?” As an engineer I get why I would want to measure my own efforts—I want to improve & I can improve faster if I know what I’m currently doing. I have no incentive to game the system. I can balance how much I want to invest in doing my work versus analyzing how I do my work.

That’s not who McKinsey is talking to. The case that keeps getting quietly mentioned is a board meeting. Sales & Engineering have both asked for more budget. Sales says, “We get $1m of sales per person, each of whom costs $500K. Give us $20m & we’ll deliver $40m in additional revenue.” Engineering says, “Um, yeah, well, uh, we need more headcount mumble mumble technical debt mumble scaling mumble keeping the lights on.” Uncomfortable!

Another way this scenario is introduced is, “The CFO wants to know if they are getting their money’s worth from Engineering.” If I was the VP Engineering in that room, I’d want to be able to answer that question. The CFO has a genuine need. The VP Eng has a genuine need. “Measuring” “productivity” may seem to meet those needs, but at enormous cost.

What’s the alternative? Listening & thinking. The best executives I’ve worked with used data, yes, but they always had direct connection to the work. They had a diverse group of individual contributors they talked to on a regular basis. Trusted relationships let them identify misaligned & perverse incentives. It may seem like scaling requires interacting with abstractions like charts & graphs, but relying solely on abstractions puts you at the mercy of whoever creates those abstractions. They have their own agenda & it might not match yours.

I love the original formulation of Goodhart’s Law: Any observed statistical regularity will tend to collapse once pressure is placed upon it for control purposes. Requires more thinking on my part, though.

I have been thinking about this for a while.

While I personally view the “Are developers being productive?” question as a smell of other problems within an organization (lack of trust, poor alignment, poor transparency), it is not unreasonable to want to know about the efficiency of the production line (as opposed to individuals - which I don't think can be measured outside of the context of a team when talking about software). For that, I personally feel that the DORA metrics do a good job of demonstrating the ability of a team to deliver "stuff" that is "stable".

A problem I see with the models that I have been involved with is that doesn't answer the question about the value of the "stuff". Doing what you are told quickly and efficiently (because, let's be realistic, nobody outside of a team REALLY cares about technical debt, they just want it faster) is great, but it won't answer the CFO's real question. Are we getting value for the investment? We had fewer defects this quarter! So? Did profits go up? In the complex systems that are most organizations, finding the correlations between effort and outcome can be difficult, which is why we fall back on simpler ideas. Tracking things like Cycle Time are indicators of problems in the line, but they do not tell you if the machine is making the right widgets. To understand the value we need to measure things like revenue, costs, customer retention/satisfaction, ...

Thank you for sharing your thoughts. Do you think we will have less discussions about engineering performance if we continously deliver value to the customers?