First published March 2018

I had a student ask today if their writing would be interesting to other folks. I answered, as I always do, with, “You & I are horrible judges of what might be interesting. Put it out there & see.”

Publish pretty much everything you write because you can’t predict what is going to be popular. There is a lower bar for quality, but barring dishonesty and literally unreadable prose, everything else should go out somewhere. Incompleteness is no excuse. Publish the first part now and the other parts later.

My desire to actually write this came, as it often does, from a series of events:

I had a tweet blow up unexpectedly. Really unexpectedly. Again. I was reminded that I can’t predict what will prove popular (for reasons I’m about to explain).

I was called humble. I explained to someone how a tweet wasn’t popular but I didn’t care because it lay on a reasonable distribution. I don’t think I’m humble, just realistic about a reality that is not yet widely shared.

I read an analysis of a blog’s readership that got this distribution wrong. They said, “Here are some typical posts except there’s this one outlier.” It wasn’t an outlier. It was right on the distribution, it just wasn’t the distribution they assumed.

I talked with a friend who writes a lot but doesn’t publish. I wanted to walk them through my thinking on publishing.

The decision to publish a piece of writing is primarily emotional. The times I’ve avoided publishing, it has been because of fear of rejection or fear of judgement. I’m not going to try to help with your emotional reactions here. I’m going to give you some logic you can inject into your thought stream.

I’ll go concrete-to-abstract:

Show you data from my tweets

Explain why the data is the shape it is

Explain why this means you should publish pretty much everything.

Warning: graphs, data, and pop statistics.

My Tweets

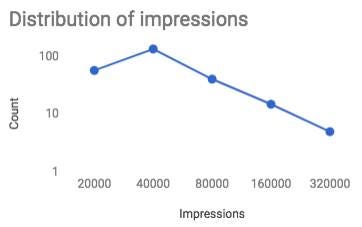

I downloaded the data from the past year of my tweets, 240 of them. I’ll focus on impressions, which I think of as the number of people a tweet was rendered for (it doesn’t count how many of those people actually viewed it, or thought about it hard, or put it into practice to transform their lives). Here is the distribution of the number of impressions per tweet:

That is, something like 60 tweets had 10K-20K impressions, 140 had 20K-40K, and so on down to the 5 that had more than 160K impressions. (I’m log-binning, which is cheating, but I’m trying to tame monkey brain, not do a science.)

Those 5 tweets on the right are not “outliers”, no, they fit right onto the distribution. 5 out of 240 tweets represent 10% of all impressions. I want to treat them as normal, not as weird irreproducible freaks.

In this kind of distribution, there is no such thing as a “normal” item. There are a bunch of smaller items and a few larger items that are systemically important. The distribution is what is normal (as in “to be expected”, not in the statistical sense).

Tug O’ War

The graph comes in two parts, the up-slope and the down-slope. The graph results from the tension between two feedback loops: the rich get richer, but the poor can only get so poor.

The right half of the graph is created because when a tweet becomes popular, it is more likely to become more popular. More retweets means more people seeing the tweet means more people retweeting. Most fires fizzle out immediately, but the ones that grow keep growing.

The left half of the graph is created because of my followers. Some percentage of them will see any tweet of mine. There is a lower limit to the number of impressions I’m going to get that has nothing to do with what I publish (in the short run).

I think of it this way: if Stephen King publishes a really horrible novel, it’s still going to sell N gajillion copies because there are just a bunch of people who will buy whatever he publishes. If he kept publishing unreadable novels, people would stop buying them, but that would be changing the shape of the curve. We’re talking about what it means to operate on this curve.

Unpredictability

I heard the story recently of a bank that took over a trading floor. They discovered that almost all profits came from 5% of the trades. The bank decreed that traders quit making the other 95% of trades.

“Only the good stuff” doesn’t work as a strategy because you don’t know, you can’t know, what constitutes good stuff until afterwards. This is as true in publishing as in trading.

It’s tough to swallow my own opinion of my pieces. I write something. I think it’s good. I learned valuable lessons in the writing. None of this has any bearing on whether other people will find it valuable.

Conversely, I can write something that I think is just a toss off, just a compilation of notes with no agenda, no poetry, no insight, and that can attract intense interest.

This was the case with my note on Mastering Programming. With 350,000 reads, this note, which I scribbled just to get it out of my head, has 10 times as many reads as my next most popular note. When I pressed Publish I debated with myself: do I want people to see something this raw from me? If I had listened to my fears, I would have missed out on getting a significant message to readers.

The tweet that triggered this note is another example. A quarter century ago I wrote some quick advice for academics submitting papers to conferences. Jo Vermeulen, a professor in Europe, mentioned this advice and provided a link to the original message. I felt a little strange retweeting a reference to my own work, but okay. I added a short summary:

The purpose of your conference paper abstract is to get your paper in the A Pile and keep it out of the B Pile.

The sentences in the abstract are:

* The problem

* Why the problem is a problem

* One Startling Sentence

* The implication of the One Startling Sentence

Again, a complete toss off. Except. Except that this tweet is one of those top 5. If I had been trying to publish “good stuff”, I would have missed it.

So What?

We’ve looked at two factors:

Response to items follows a long-tailed distribution.

Nobody can predict beforehand where any given item will fall on the distribution.

Add those together and my best strategy, if I want to maximize the attention given to what I write, is to publish everything.

There are a couple of provisos to what I mean by “everything”. If you publish too many items or if the items are horrible, then you end up changing the shape of the curve for the worse. A worse distribution, even covering more items, results in less attention.

Other than that? Yep. Publish it all. Follow up on the most popular items (this is one part I’m terrible at). But if it’s not so bad as to actively damage your reputation, get it out there and pay attention to the feedback.

I will note that there are many motivations for writing (photographing, painting, recording, etc.) that have nothing to do with getting the most attention. Sometimes I just want a little project where I feel a sense of control. That’s okay, as long as I admit it to myself. I don’t want to be the self-martyred forgotten artist. “If only the world understood my genius...” Pffft.

P.S. A Prediction

From the tweet data, I can predict that I will soon have a tweet with more than 300K impressions. This says nothing about me personally. I’m not just that awesome. I won’t write a tweet of surpassing beauty. I won’t suddenly get the hang of tweeting. Impressions follow a distribution and there is a hole in the distribution above. That hole will be filled in, and when it is I will be a surprised as anyone about what fills it.

I haven’t run the numbers for all 12 years of my tweeting. This year, however. I did have a tweet hit 1.4 million impressions. Right on the distribution.

P.P.S. The Numbers Game

After the 300K impression tweet, if I want a tweet with 600K impressions I have no choice but to fill in the rest of the distribution. That means lots, like many hundreds, of tweets that don’t blow up. There is no shortcut. I could probably game the metrics, but then I ruin any chance of learning lessons from the numbers.

I first started blogging back in 2002 (or 2003?) because my boss at the time, Jeremy Allaire, was very excited about blogging as a medium and wanted his whole engineering team at Macromedia to "start a blog and write something every day!". It became part of my daily work routine: take notes about what I do and what I think and what I read -- and compose something, short or long, every day. I had an alarm in my work calendar at 10:30 am "blog!". And for several years I kept it up. Sometimes it was just a sentence or two, or a link; sometimes it was an essay. I changed platforms several times over the last two decades and a lot of that writing is only available on The Wayback Machine, I suspect. I have an almost complete archive of one database of posts (from maybe 2004 to about 2014, I think) and occasionally republish pieces from that -- but I work in a completely different technology stack these days so a lot of the nuts and bolts of the old blog aren't relevant to many people anymore (or so I tell myself).

I was nearly always surprised at which posts got engagement and which didn't. Sometimes I'd spend hours writing what I thought was an excellent, insightful post only to get... crickets... and sometimes a quick paragraph I'd dashed off would generate a flood of commentary and response pieces on other blogs. As you say, you can never predict what will catch fire and what won't...

p.s., Stephen King's "On Writing" has similar advice: write something every day -- it might be good, it might not be good, and you might not be the best judge of that.

Hey Kent, your insights on publishing everything resonate so well. Embracing unpredictability and putting your work out there can often lead to unexpectedly impactful results.