Originally published March 2017

This is me reminding myself that I don’t need rigid rules to make myself safe. I can experiment & get really excited. I won’t just continue pursuing a failing experiment forever because I have so many other things I could be working on. One of them will tug me.

Our biggest costs are opportunity costs

One of the joys of exploring a new idea like 3X is that you get reminded, over and over, just how wrong you usually are. A colleague offered me one of these enlightenment gifts the other day and I wanted to share.

One of the challenges in Exploring is simultaneously:

Treating your experiments seriously, as if they are going to yield the desired hypergrowth, and

Treating them as experiments, likely to “fail” and worth limited investment.

You may feel certain that people are going to love love love this next feature, but if they don’t, you are better off dropping it and moving on to the next feature.

This is a genuine dilemma. The next little tweak might start a wildfire, but there is always a next little tweak. At the same time, there are hundred other things you could be working on, any one of which might be huge. At the time you decide to persevere or punt, the information simply doesn’t exist to make a correct, rational decision.

So, how do you decide?

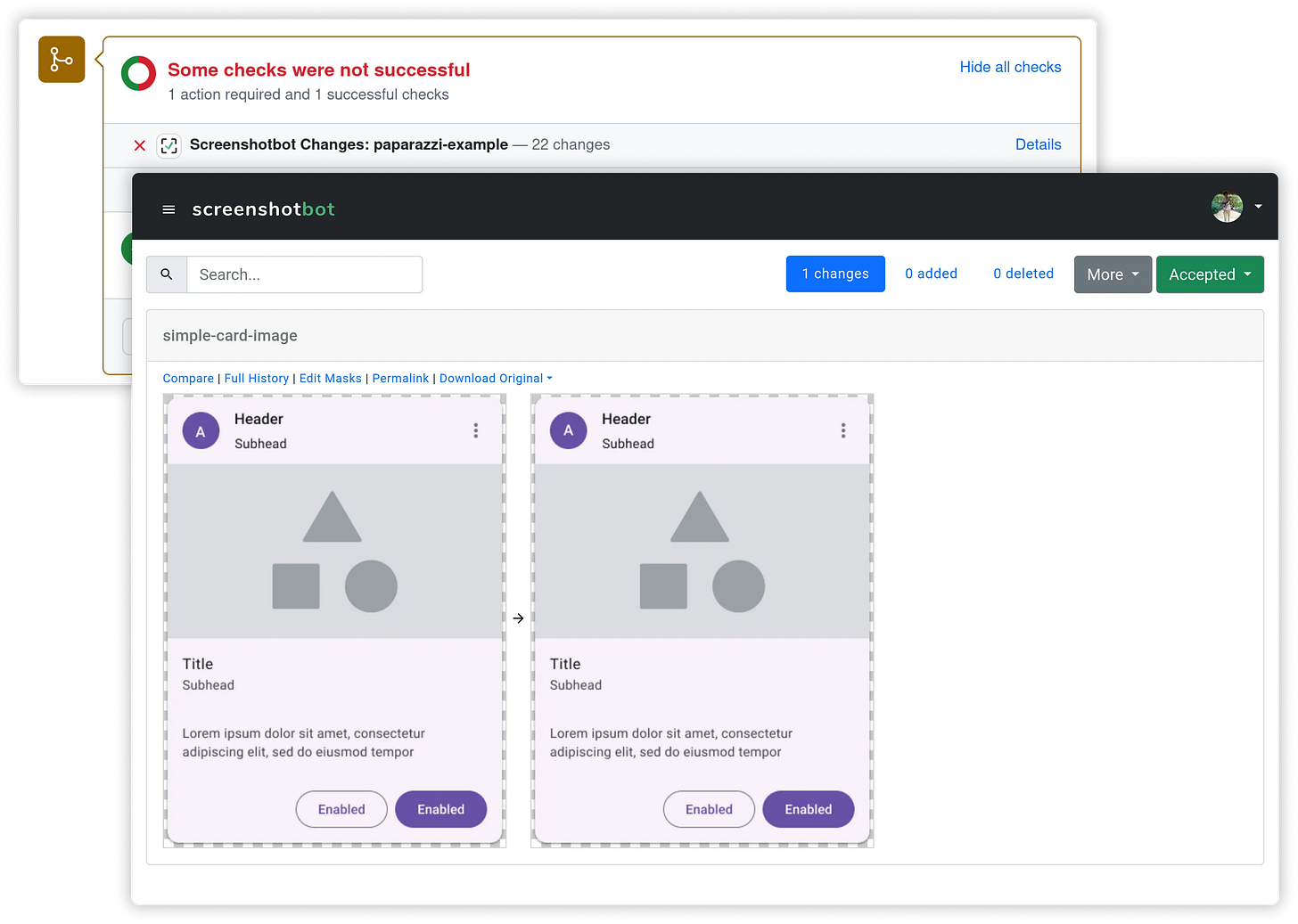

Thanks to this week’s sponsor, Screenshot Bot. Arnold Noronha, the founder, was a student of mine at Facebook.

Screen shot tests for mobile apps (and more)

Want to know when something has accidentally changed in your mobile app? Screenshot tests occupy a unique point in the space of tests—easy to write, predictive, & automated.

Use https://screenshotbot.io/tidyfirst to signup to get 20% off your first year.

My answer so far in discussing 3X has been timeboxing. Before you start an experiment, you specify how much time or money you’re going to spend on it. When the timer dings, you put your pencil down, roll back from your desk, heave a big sigh, maybe shed a tear, and then roll up and get started on the next thing.

Timeboxing is based on the sunk cost fallacy, the cognitive bias where we assign too large a value or too great a chance of success to an activity that has already cost us a lot. The end of the timebox is intended to give rational thought a chance to intervene, to evaluate more accurately the chance of success.

My friend pointed out that there another rationalizing force at work: FOMO. Every day you spend in this project is a day you aren’t spending on that. And that. And that. If a project isn’t going well, pretty soon you’re going to reach the margin where another project starts looking mighty tasty.

An important question to consider when the timer goes ding is "are we frustrated with how long it took to execute those ideas?"

In the Explore phase I mostly don't care about technical debt, as any investment I make is likely to be thrown away soon.

But the moment we get to the end of a timeline and think "that was a small idea but it took too long" we should pause and address some of the friction.

I just want to say that the headline on this caused me distress, because I thought you were shutting down the substack! <3