The consultancy giant has devised a methodology it claims measures software developer productivity. They only measure activity, not productivity from a business perspective. And measuring activity comes with costs & risks they do not address. Here’s how we think about measurement. Part 1. (Gergely’s version of this post is here.)

At Facebook we [Kent here] instituted the sorts of surveys McKinsey recommends. That was good for about a year. The surveys provided valuable feedback about the current state of developer sentiment.

Then folks decided that they wanted to make the survey results more legible so they could track trends over time. They computed an overall score from the survey. A 4.5 became a 4. What happened? Very reasonable thing to do. That was good for another year

Then those scores started cropping up in performance reviews, just as a "and they are doing such a good job that their score is 4.5". That was good for another year.

Then those scores became goals. “Move from 4.2 to 4.5 during this performance review period.” And the scores started getting rolled up. A manager’s score was the average of their reports’ scores. A director's score was the average of their reporting managers’ scores.

Now things started getting unhinged. Directors put pressure on managers for better scores. Managers started negotiating with individual contributors for better survey scores. “Give me a 5 & I’ll make sure you get an ‘exceeds expectations’.” Directors started cutting managers & teams with poor scores, whether those cuts made organizational sense or not.

Things went from, “we’d like to know how things are going,” to, “we know even less about how things are going. But they are definitely going worse because people are now gaming the system.” How did this occur? Well, because we started to measure & incentivize (with money & status) changes in the measures! And measuring leads to behavior change – behavior change including coming up with creative ways to improve those measurement scores even at the expense of results that everyone agrees matter.

In this two-part article, we seek to arm engineering leaders with perspectives to the question: Can you measure developer productivity? It’s the sum of our viewpoints, professional experiences, and what we’ve seen work, firsthand:

Kent Beck brings 40 years of software engineering experience, and has tried, failed, and tried again to measure developer productivity for almost all this time.

Gergely Orosz brings 15 years of software engineering experience, including 5 years’ managing engineering teams.

Two weeks ago, McKinsey published the article “Yes, you can measure software developer productivity.” In it, the company claimed it has an approach for measuring software developer productivity that nearly 20 companies already use, and that the consultancy is ready to extend the roll out of the custom approach.

As tempting as it is, we won’t go into a detailed critique of the McKinsey article and the measurement methodology. The thinking that’s evident in the article is absurdly naive and ignores the dynamics of high-performing software engineering teams. But it was written for a reason: CEOs and CFOs are increasingly frustrated by CTOs throwing up their hands and saying software engineering is too nuanced to measure, when sales teams have individual measurements and quotas to hit, as do recruitment teams in the number of positions to fill. The executive reasoning goes: if other groups can measure individual performance, it’s absurd that engineering cannot.

The reality is engineering leaders cannot avoid the question of how to measure developer productivity, today. If they try to, they risk the CEO or CFO turning instead to McKinsey, who will bring their custom framework, deploy it – even as the CTO protests – and start reporting on custom McKinsey metrics like “Developer Velocity Benchmark Index,” “Contribution Analysis,” and “Talent Capability.”

We believe that introducing such a framework is wrong-headed and certain to backfire. The McKinsey framework will most likely do far more harm than good to organizations – and to the engineering culture at companies. Such damage could take years to undo. So let’s get around to answering this question without evasion, and give demanding CEOs and CFOs what they want.

We cover:

A mental model of the software engineering cycle

Where does the need for measuring productivity come from?

How do sales and recruitment measure productivity so accurately?

Measurement tradeoffs in software engineering

Who is this article for? We wrote this article for software developers and engineering leaders, and anybody who cares about nurturing high-performing software development teams. By “high performing” we mean teams where developers satisfy their customers, feel good about coming to work, and don’t feel like they’re constantly measured on senseless metrics which work against building software that solves customers’ problems. Our goal is to help hands-on leaders to make suggestions for measuring without causing harm, and to help software developers become more productive.

When reading articles like McKinsey’s, keep in mind they’re written for a very different, and specific, audience: untechnical CEOs and CFOs with little to zero experience with software development. Engineering is just another department. They need to treat engineering the same way they treat Sales or Recruitment – and will do so, regardless of the damage misconceived frameworks do to development culture.

A mental model of the software engineering value

How does software engineering create value? Take the typical example of building a feature, then launching it to customers, and iterating on it. What does this cycle look like? Say we’re talking about a pretty autonomous and empowered software engineering team working at a startup, who are in tune with customers:

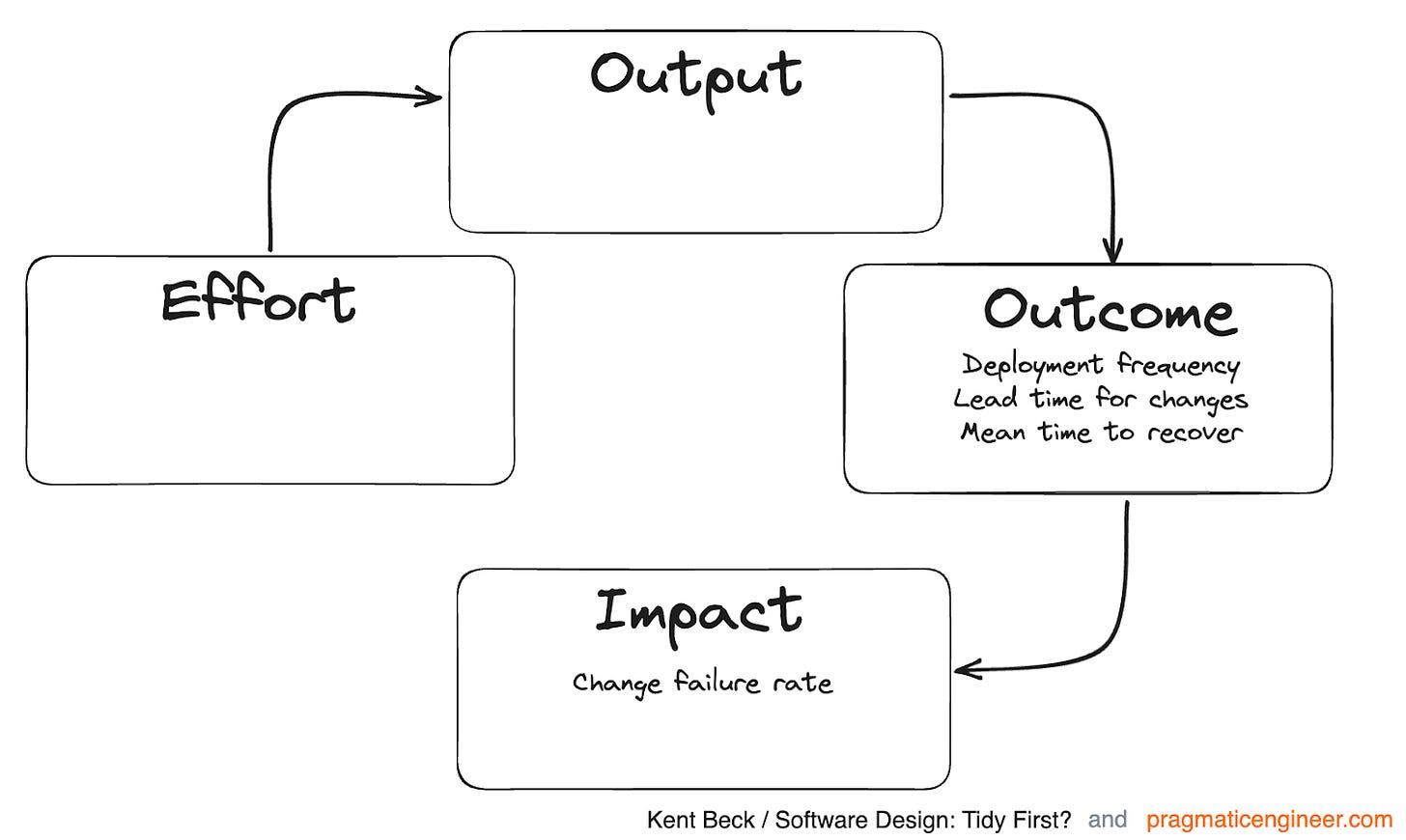

We start by deciding what to do next, and then we do it. This is the effort like planning, coding and so on. Through this effort, we produce tangible things like the feature itself, the code, design documents, etc. These are the output. Customers will behave differently as a result of this output, which is our outcome. For example, thanks to the feature they might get stuck less during the onboarding flow. As a result of this behavior change, we will see value flowing back to us like feedback, revenue, referrals. This is the impact.

So let’s update our mental model with these terms:

The effort-output-outcome-impact model describes software engineering, and works just as well for smaller tasks as it does to model thinking about feature development, or shipping complex projects.

We reference this model throughout this article.

Where does the need for measuring productivity come from?

Before we answer how to measure, let’s start with the more important question:

Who wants to measure productivity, and why?

This is such an important question to start with. The answer will differ dramatically, depending on who’s asking, and what the goal of the question is. Here’s a few common examples:

#1: a CTO who wants to identify which engineers to fire. “How can I measure the productivity of engineers in the organization, to identify the least productive 10%, and let them go?”

Unfortunately, this case is timely in the wake of recent layoffs across the tech industry. Here are some ways to answer it:

Identify the lowest performers based on the latest performance review scores. This approach uses historical data that is likely somewhat outdated.

Decide based on tenure, and lay off based on the “last in, first out” method. This uses no performance-related data and simply assumes that the exit of recent joiners will affect productivity less.

Decide on a few easy-to-measure metrics like the number of pull requests, number of tickets closed, and so on. Basically, to decide by effort and output.

Ask managers to identify the number of engineers to be let go. This approach can harness team dynamics and unquantifiable information like a manager knowing which engineers are about to hand in their resignation, which quantitative metrics miss.

With layoffs, team dynamics are impacted, and any approach which fails to take this into account, is likely to result in a less than ideal outcome. At the same time, layoffs often come with constraints, like senior leadership not wanting to get line managers involved. As a result, decisions are often made based on metrics known to be incorrect.

#2: To compare two investment opportunities. “How can I measure the productivity of teams, and allocate additional headcount to the team that will make the most efficient use of additional headcount?”

To answer this question, you want to compare the return on investment. This is not a question about productivity, it’s about the impact of allocating more headcount to one team or another

#3: To manage performance. “How can I measure engineers’ productivity to identify and reward the top 10%, and to identify the bottom quarter in order to debug and improve their performance?”

There are plenty of ways to go about measuring performance, and doing so with metrics is possible, though error prone. A hands-on manager can immediately name their bottom and top performers, and then examine and debug outputs, and look closer at how engineers do their work (their effort.) Performance calibrations are a standard way to do this.

#4: a software engineer who wants to grow at their craft. The question could be: “How can I measure my own productivity, and which metrics can I improve to become a better engineer?” This is a question more engineers should ask of themselves! Here are two helpful approaches:

Aim to only have one red test at a time when using test driven development (TDD). This approach measures both effort and output. Get to the point where you can confidently, deliberately and consistently have one red test, when you expect one red test.

Set a goal to merge a pull request every day, and track this goal over a week. This measure includes both effort and output. This goal forces you to do smaller commits, which are easier to review and get signed off quicker. It also pushes you to write code that’s correct and follows team standards.

As long as you keep tracking these “scores” and work on improving them, you’ll almost certainly improve your efficiency as a software engineer.

But what would happen if you showed these metrics to your manager and your performance was then judged by them? It would be a disaster: you’d be measured not on outcomes or impact, but by output. When you experiment with approaches – for example, learning a new language to help a team in need – then your output could drop, even though you are helping the team achieve a better outcome!

Why can sales and recruitment measure productivity so accurately?

As the software engineering industry, we should collectively admit we’ve done a much worse job of measuring productivity down to the individual level, than other functions have. Take sales as an example. Here is Kent’s account of the level of accountability Sales operates at, from a meeting of sales and engineering leadership at one of his past companies:

“I clearly remember this meeting where it was engineering and sales leadership reporting on progress. Each person from the sales team spoke and gave an update which went something like this:

‘My team’s target for the quarter was $600K, and we delivered $520K. I take accountability for the miss. Here are the reasons it happened, and here is my plan of what I’m changing to hit next quarter’s goal of $650K. Additionally, here is a two-quarter-long initiative I am putting in place, which I expect will bring an incremental $100K for each quarter, once complete. Any questions?’

If anyone had questions, the sales leader would drill down all the way to the individual level – which sales reps were above quota and which were below it, and by how much – and do so in a way that everyone in the room understood.

And then, it was engineering’s turn. My goodness, the contrast was stark. The typical engineering update went something like this:

‘So, this quarter we shipped Feature A, and we are slightly behind on some tech debt migration, and next quarter we’ll ship Feature B and catch up on the migration. Any questions?’

If anyone had questions about some delay, the answer was never about individuals – as with sales – and usually included factors like unforeseen difficulties, tech debt, APIs; all things which non-engineers in the room didn’t really understand.”

The level of accountability which sales and customer support work with is on a completely different scale from what a CEO observes from engineering. But when the CEO examines overall departmental costs, engineering probably costs more than sales!

It’s not just sales that demonstrates higher levels of accountability. Recruiting teams have targets for “heads to fill.” A recruitment team can without hesitation answer the question of what percentage of their targets have been met, how many more recruiters they need to meet aggressive hiring targets, and to identify the top and the bottom recruiters, purely based on metrics.

Let’s put ourselves in the shoes of a CEO. Sales has ways to clearly measure productivity, as does recruitment. So why not engineering?

Let’s return to our effort-output-outcome-impact mental model of how software engineering works. We can apply this model to sales and recruitment. The sales team measures itself by deals closed, so where does this metric go in the model? It falls into “outcome” or “impact:”

What about the recruitment team’s main metric: the number of heads filled? It’s also categorized as “impact:”

We can repeat this exercise for other functions with high accountability in how they work. For example, customer support can be measured by the number of tickets closed (an outcome), the time it takes to close a ticket (also an outcome,) and by customer satisfaction scores (impact.)

Neither Kent nor I have seen accountable teams within tech companies which are not measured by outcome and impact. In order to make software engineering more accountable, we need to look at how to do this.

Measurement tradeoffs in software engineering

One popular framework to measure software engineering team efficiency is the DORA framework. Let’s map out the focus of this framework measurement:

The 4 DORA metrics: each measures outcome or impact

All DORA metrics measure outcomes or impact.

Let’s look at another way to measure developer productivity: the SPACE framework. It seeks to capture satisfaction, performance, activity, communication, and efficiency (SPACE.) It’s not only outcomes and impact, as with DORA. The SPACE framework does not outline definite metrics – but gives example ones. Several of the metrics come with a warning, like measuring lines of code. Metrics that come with a warning from the SPACE framework authors – such as the ‘lines of code’ metric – tend to measure effort or outcome.

One critique of McKinsey’s system we have is that nearly every single one of its custom metrics which differ from DORA and SPACE metrics, measure effort or output:

4 out of the 5 new metrics suggested by McKinsey’s measure effort or output

What’s wrong with this approach? First, the only folks who care about these metrics are the people collecting them. Customers don’t care. Executives don’t care. Investors don’t care. Second, and most crucially, collecting & evaluating these metrics interferes with the team delivering on the measures downstream folks actually do care about, like profitability.

Why is McKinsey adding ways to measure effort? One reason is that it’s the easiest thing to measure! But the McKinsey approach ignores an important truth: the act of measurement changes how developers work, as they try to “game” the system.

The earlier in the cycle you measure, the easier it is to measure. And also the more likely that you introduce unintended consequences. Let’s take the extreme of measuring only profits. The good news is that everyone is aligned, across the company! The bad news: attributing who contributed how much to the profit is nearly impossible! You can ‘fix’ the attribution question by measuring outputs, or effort. But the cost is that you change people’s behavior, as it incentivizes them to game the system to ‘score’ better on those metrics:

Measurement tradeoffs: capturing impact and outcomes boosts alignment, but makes it harder to attribute individuals’ contribution. But measuring earlier in the cycle creates unintended consequences, as people stop caring about group or company goals

Let’s take the case of a company that’s reasonably profitable and in the upper quartile for the industry. The company’s leadership dislikes being unable to attribute individuals’ performance in contributing to profitability.

Would you be tempted to screw up your company’s business by introducing micro-measuring? Hell no!

We urge engineering leaders to look to outcome and impact measurements, to identify what to measure. It’s true that it is tempting to measure effort. But there’s a reason why sales and recruitment teams are not judged by their performance in being in the office at 9am sharp, or by the number of emails sent – which are both effort or output.

So which outcomes and impacts can be measured for engineering teams? DORA and SPACE give some pointers, and we offer two more:

Please the customer at least once per team, per week. This output might not sound so impressive, but in practice is very hard to achieve. The most productive teams – and nimble companies – can pull this off, though. If you consider why a startup moves so fast and executes so well, it’s because they have to do so out of necessity, even if they do not measure this.

Delivering business impact committed to by the team. There is a good reason why “impact” is so prevalent at the likes of Meta, Uber, and other fast-moving tech companies. By rewarding impact, the business incentivizes software engineers to understand the business, and to prioritize helping it reach its goals. Is shipping a $2M/year cost-saving exercise via a configuration change, less valuable than shipping a $500K/year cost-saving exercise that takes 5 engineering months? No! You don’t want to focus solely on impact, but not focusing on the end goal of delivering business value is a poor choice.

Takeaways

There is, undoubtedly, mounting pressure from the business in wanting to quantify the productivity of software development teams. Companies like McKinsey are responding to this clear demand by providing frameworks that promise to do exactly this.

Measuring effort and output is attractive. These come with tradeoffs that will negatively impact the engineering culture. As engineering leaders: be sure to consider this tradeoff, and how it could change the incentives of developers.

In Part 2 of this article – coming out on Thursday –, we will go into the dangers of only measuring outcomes and impact; and offer our answer to the question on whether & how to measure developer productivity.

(Kent here: I am writing this with Gergely Orosz and his valuable The Pragmatic Engineer stack. Please consider subscribing. Thursday’s piece will give you my personal takes on what to do & what not to do when it comes to measurement.)

Recruiters and sales people also game the system. If recruiter is measured by lead time and closure of positions, we end up hiring the below-average people to fill in the slots. And talk about system dynamics from there.

This is great! Measuring output is an artifact from the pre-digital industrial age, when output was a decent predictor of outcome. Operational risk was paramount. (If we can produce a black Model T efficiently enough, the middle class will buy.)

Entire companies are structured around optimizing efficiency of output. This makes measuring efficiency of outcomes difficult. Engineering teams may very efficiently build features customers don’t care about. This means you need other disciples involved. Company structure makes this difficult.