Earn *And* Learn

What Game Are We Playing?

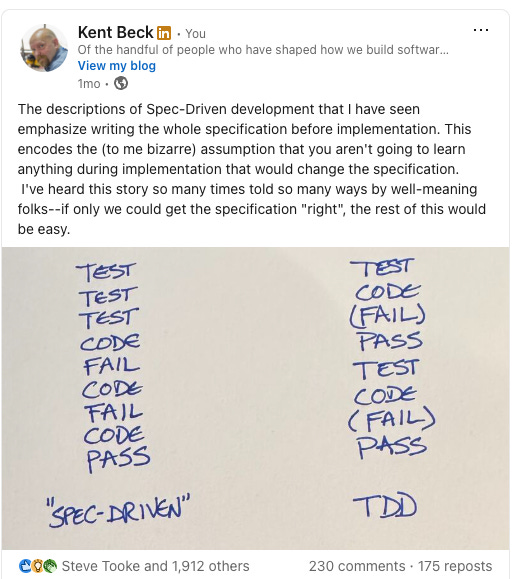

Spec-driven or not spec-driven is not the question. The first question is, “What game are we playing?” Here’s the game I’m playing when I develop software, with or without the genie. I call it The Compounding Game:

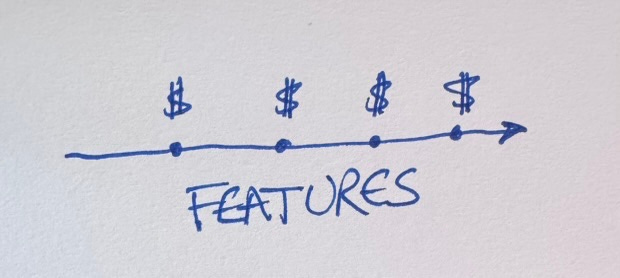

The first thing we finish will earn the resources for the next thing which will earn the resources for the next.

Different Game, Different Rules

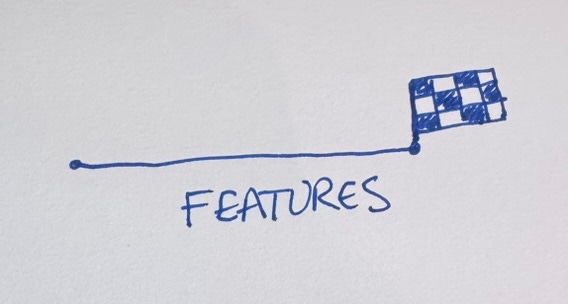

Here’s The Finish Line Game, a different software development game:

We want software that does X. Once we’ve reached X we’re done. It happens. I have some data. I need it munged. I write a munging script. Finito. I’ll never use that script again.

The hidden assumption behind this style of spec-driven development is that we’re playing The Finish Line Game. Get the spec right. Get the desired software. Done. No need to consider the future because there won’t be one.

Failure & Success in the Finish Line Game

If you’re playing The Finish Line Game, you can still fail. Design can be so bad you don’t cross the finish line. Tests can be so bad that you don’t notice that you haven’t crossed the finish line. The “finish line” itself can shift without you noticing.

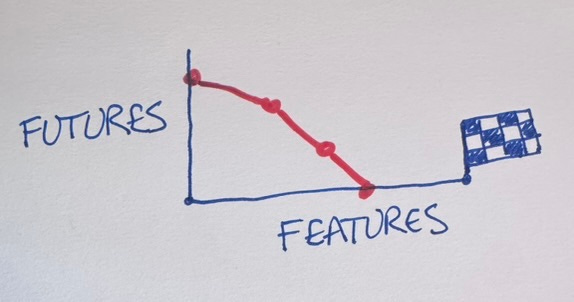

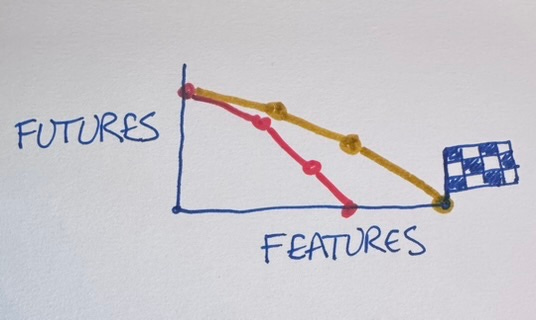

In the Tidy First world, we illustrate by contrasting “futures” & “features”. Futures are what all you can implement next. The genie is no good at managing futures. If you’re playing The Finish Line Game, you’re betting that features will cross the finish line before futures run out.

This is “better agent.md file” territory. If we leave the genie autonomous, can we nudge its work to be good enough not to fail? Sometimes yes, sometimes no (in my experience). And the genie keeps getting better. But it’s still the same Finish Line Game.

Playing The Compounding Game

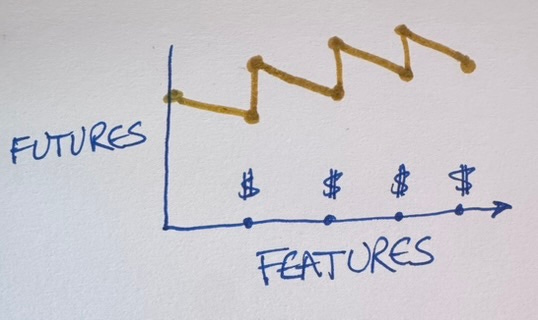

Just as football tactics won’t work on a baseball field, spec-driven development doesn’t work if you’re playing The Compounding Game. A better spec will never get you from dollar sign N to dollar sign N+1 forever. A better agent file won’t extend the lifespan of the system long enough to get from N to N+1. At some point the complexity will exceed the genie’s capacity & it’s game over with lots of dollar signs left to play for.

Instead, playing The Compounding Game requires as much investment in futures as in features. The two alternate. (Hence the “tidy first” connection—tidying is part of investing in the future.)

We’ll talk more about those vertical shifts more as we go along:

What senior engineers do to shift vertically

What junior engineers do to shift vertically

What tools to write

What practices to apply

How to get the genie to help

This really clarifies something I've experienced more than once joining companies with a lot of legacy code. More new functionality is always wanted, but building on the existing codebase had already consumed too many of their futures. We had to invest in refactoring and testing first, which felt risky because it delayed features. Your features/futures framing names exactly what I was protecting -- the capacity to keep building after that first feature shipped.

At one company after we did this there was push to build a vast feature, something like 1.5 team-years worth of work. A clever product manager on the team led the fast delivery of the smallest unit of that feature that could provide value, and then found customers used it and liked it. She asked them what else it needed to do, and one enhancement was requested far more than any other. We built that. Total time: three weeks. Customers all but stopped asking for more. They never needed the rest of what we initially envisioned this feature to be! We preserved futures by building only what was actually needed. Reading this makes me realize we were alternating between features and futures without having the language for it. Thank you for giving me that language.

This is good and helpful.

At the same time I’ve found that so much of what happens next depends on the makeup of my team. What values do we share?

I sometimes wonder if I could convince people that gravity exists if they aren’t already interested in the topic.

I could think futures vs features are important. Meanwhile my team mates might be more oriented towards new threading models in Java 25. If that’s the case we’ll have hard time navigating the features vs futures space.

I struggle with this aspect of work more than anything. I guess I’m asking how to apply this in a team setting when it’s not even something on people’s radar.