Don’t Cross the Beams

Avoid Interference Between Horizontal and Vertical Refactorings

Originally published September 2011. Folks don’t talk much about dimensions of refactoring, but moving code up & down the call stack is a different beast than making changes across a bunch of similar code (coupling). Become aware of the difference & post your examples in the comments!

As many of my pair programming partners could tell you, I have the annoying habit of saying “Stop thinking” during refactoring. I’ve always known this isn’t exactly what I meant, because I can’t mean it literally, but I’ve never had a better explanation of what I meant until now. So, apologies y’all, here’s what I wished I had said.

One of the challenges of refactoring is Succession–how to slice the work of a refactoring into safe steps and how to order those steps. The two factors complicating succession in refactoring are efficiency and uncertainty. Working in safe steps it’s imperative to take those steps as quickly as possible to achieve overall efficiency. At the same time, refactorings are frequently uncertain–”I think I can move this field over there, but I’m not sure”–and going down a dead-end at high speed is not actually efficient.

Inexperienced empirical designers can get in a state where they try to move quickly on refactorings that are unlikely to work out, get burned, then move slowly and cautiously on refactorings that are sure to pay off. Sometimes they will make real progress, but go try a risky refactoring before reaching a stable-but-incomplete state. Thinking of refactorings as horizontal and vertical is a heuristic for turning this situation around–eliminating risk quickly and exploiting proven opportunities efficiently.

The other day I was in the middle of a big refactoring when I recognized the difference between horizontal and vertical refactorings and realized that the code we were working on would make a good example (good examples are by far the hardest part of explaining design). The code in question selected a subset of menu items for inclusion in a user interface. The original code was ten if statements in a row. Some of the conditions were similar, but none were identical. Our first step was to extract 10 Choice objects, each of which had an isValid method and a widget method.

before:

if (...choice 1 valid...) { add($widget1); } if (...choice 2 valid...) { add($widget2); } ...

after:

$choices = array(new Choice1(), new Choice2(), ...); foreach ($choices as $each) if ($each->isValid()) add($each->widget());

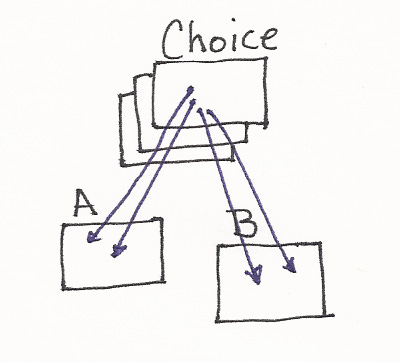

After we had done this, we noticed that the isValid methods had feature envy. Each of them extracted data from an A and a B and used that data to determine whether the choice would be added.

Choice1 isValid() { $data1 = $this->a->data1; $data2 = $this->a->data2; $data3 = $this->a->b->data3; $data4 = $this->a->b->data4; return ...some expression of data1-4...; }

We wanted to move the logic to the data.

Choice1 isValid() { return $this->a->isChoice1Valid(); } A isChoice1Valid() { return ...some expression of data1-2 && $this-b->isChoice1Valid(); }

Succession

Which Choice should we work on first? Should we move logic to A first and then B, or B first and then A? How much do we work on one Choice before moving to the next? What about other refactoring opportunities we see as we go along? These are the kinds of succession questions that make refactoring an art.

Since we only suspected that it would be possible to move the isValid methods to A, it didn’t matter much which Choice we started with. The first question to answer was, “Can we move logic to A?” We picked Choice. The refactoring worked, so we had code that looked like:

A isChoice1Valid() { $data3 = $this->b->data3; $data4 = $this->b->data4; return ...some expression of data1-4...; }

Again we had a succession decision. Do we move part of the logic along to B or do we go on to the next Choice? I pushed for a change of direction, to go on to the next Choice. I had a couple of reasons:

The code was already clearly cleaner and I wanted to realize that value if possible by refactoring all of the Choices.

One of the other Choices might still be a problem, and the further we went with our current line of refactoring, the more time we would waste if we hit a dead end and had to backtrack.

The first refactoring (move a method to A) is a vertical refactoring. I think of it as moving a method or field up or down the call stack, hence the “vertical” tag. The phase of refactoring where we repeat our success with a bunch of siblings is horizontal, by contrast, because there is no clear ordering between, in our case, the different Choices.

Because we knew that moving the method into A could work, while we were refactoring the other Choices we paid attention to optimization. We tried to come up with creative ways to accomplish the same refactoring safely, but with fewer steps by composing various smaller refactorings in different ways. By putting our heads down and getting through the other nine Choices, we got them done quickly and validated that none of them contained hidden complexities that would invalidate our plan.

Doing the same thing ten times in a row is boring. Half way through my partner started getting good ideas about how to move some of the functionality to B. That’s when I told him to stop thinking. I don’t actually want him to stop thinking, I just wanted him to stay focused on what we were doing. There’s no sense pounding a piton in half way then stopping because you see where you want to pound the next one in.

As it turned out, by the time we were done moving logic to A, we were tired enough that resting was our most productive activity. However, we had code in a consistent state (all the implementations of isValid simply delegated to A) and we knew exactly what we wanted to do next.

Conclusion

Not all refactorings require horizontal phases. If you have one big ugly method, you create a Method Object for it, and break the method into tidy shiny pieces, you may be working vertically the whole time. However, when you have multiple callers to refactor or multiple implementors to refactor, it’s time to begin paying attention to going back and forth between vertical and horizontal, keeping the two separate, and staying aware of how deep to push the vertical refactorings.

Keeping an index card next to my computer helps me stay focused. When I see the opportunity for a vertical refactoring in the midst of a horizontal phase (or vice versa) I jot the idea down on the card and get back to what I was doing. This allows me to efficiently finish one job before moving onto the next, while at the same time not losing any good ideas. At its best, this process feels like meditation, where you stay aware of your breath and don’t get caught in the spiral of your own thoughts.

Yes. I think that instead of saying "Stop thinking!", this might inspire us to respond with a more positive tone, like "Great idea! Let's write it down on this list, and get back to it when we've finished this sequence of moves." IE: Finish one thing before going off on some tangent.

("Squirrel!!!)

While reading your post, a mental image of Breadth-First Traversal came to my mind. Thanks for the index card tip!