What follows is NOT how you should do TDD. Take responsibility for the quality of your work however you choose, as long as you actually take responsibility.

What follows is my response to “TDD suckz dude because <something that isn’t TDD>”, a frequent example being, “…because I hate writing all the tests before I write any code.” If you’re going to critique something, critique the actual thing.

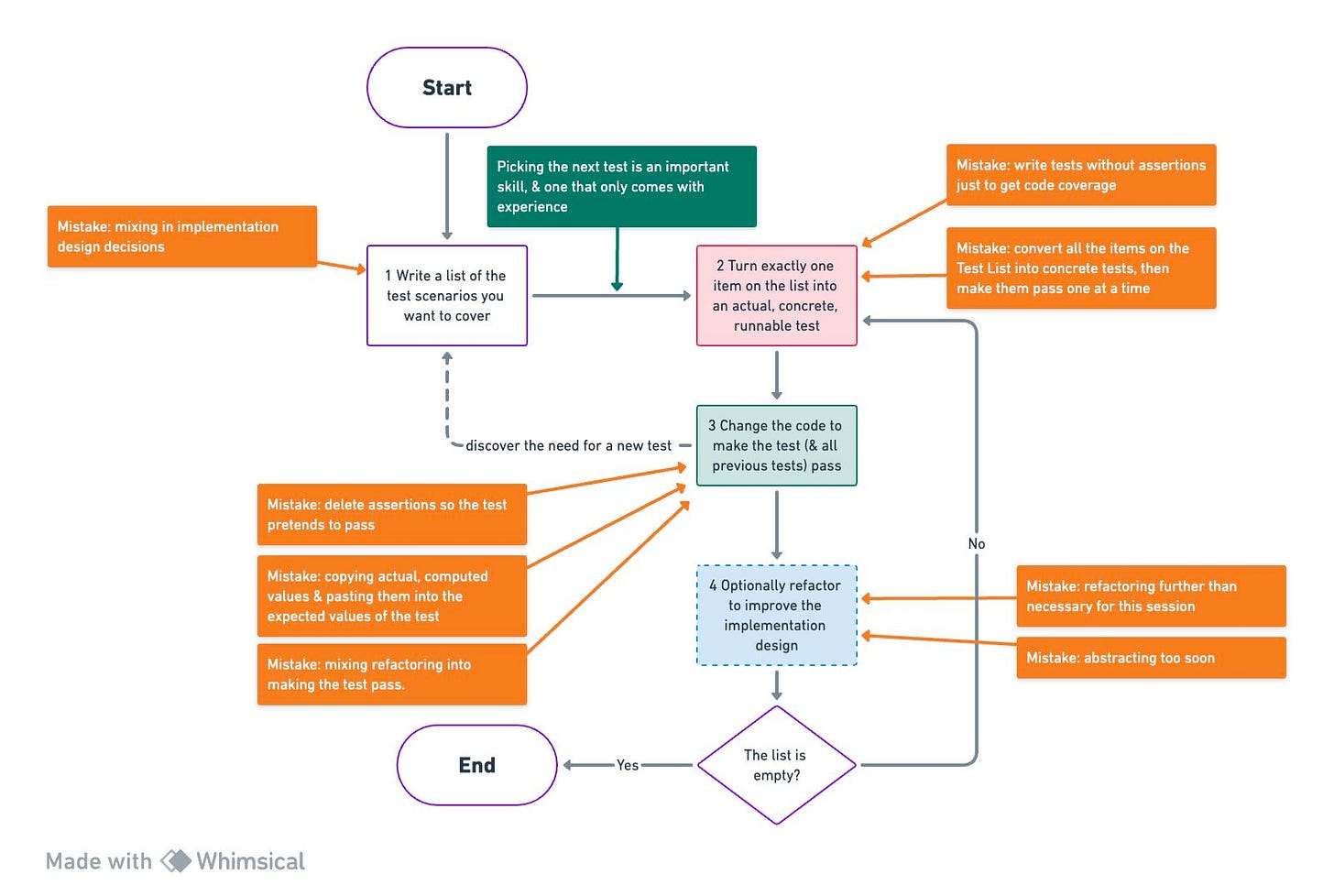

Write a list of the test scenarios you want to cover

Turn exactly one item on the list into an actual, concrete, runnable test

Change the code to make the test (& all previous tests) pass (adding items to the list as you discover them)

Optionally refactor to improve the implementation design

Until the list is empty, go back to #2

Intro

summarized this post graphically:In my recent round of TDD clarifications, one surprising experience is that folks out there don’t agree on the definition of TDD. I made it as clear as possible in my book. I thought it was clear. Nope. My bad.

If you’re doing something different than the following workflow & it works for you, congratulations! It’s not Canon TDD, but who cares? There’s no gold star for following these steps exactly.

If you plan on critiquing TDD & you’re not critiquing the following workflow, then you’re critiquing a strawman. That’s my point in spending some of the precious remaining seconds of my life writing this—forestalling strawmen. I’m not telling you how to program. I’m not charging for gold stars.

I try to be positive & constructive as a habit. By necessity this post is going to be concise & negative. “People get this wrong. Here’s the actual thing.” I don’t mean to critique someone’s workflow, but sharpen their understanding of Canon TDD.

Overview

Test-driven development is a programming workflow. A programmer needs to change the behavior of a system (which may be empty just now). TDD is intended to help the programmer create a new state of the system where:

Everything that used to work still works.

The new behavior works as expected.

The system is ready for the next change.

The programmer & their colleagues feel confident in the above points.

Interface/Implementation Split

The first misunderstanding is that folks seem to lump all design together. There are two flavors:

How a particular piece of behavior is invoked.

How the system implements that behavior.

(When I was in school we called these logical & physical design & were told never to mix the two but nobody ever explained how. I had to figure that out later.)

The Steps

People are lousy computers. What follows looks like a computer program but it’s not. It’s written this way in an attempt to communicate effectively with people who are used to working with programs. I say “attempt” because, as noted above, folks seem prone to saying, “TDD suckz, dude! I did <something else entirely> & it failed.”

1. Test List

The initial step in TDD, given a system & a desired change in behavior, is to list all the expected variants in the new behavior. “There’s the basic case & then what if this service times out & what if the key isn’t in the database yet &…”

This is analysis, but behavioral analysis. You’re thinking of all the different cases in which the behavior change should work. If you think of ways the behavior change shouldn’t break existing behavior, throw that in there too.

Mistake: mixing in implementation design decisions. Chill. There will be plenty of time to decide how the internals will look later. You’ll do a better job of listing tests if that’s all you concentrate on. (If you need an implementation sketch in Sharpie on a napkin, go ahead, but you might not really need it. Experiment.)

Folks seem to have missed this step in the book. “TDD just launches into coding 🚀. You’ll never know when you’re done.” Nope.

2. Write a Test

One test. A really truly automated test, with setup & invocation & assertions (protip: trying working backwards from the assertions some time). It’s in the writing of this test that you’ll begin making design decisions, but they are primarily interface decisions. Some implementation decisions may leak through, but you’ll get better at avoiding this over time.

Mistake: write tests without assertions just to get code coverage.

Mistake: convert all the items on the Test List into concrete tests, then make them pass one at a time. What happens when making the first test pass causes you to reconsider a decision that affects all those speculative tests? Rework. What happens when you get to test #6 & you haven’t seen anything pass yet? Depression and/or boredom.

Picking the next test is an important skill, & one that only comes with experience. The order of the tests can significantly affect both the experience of programming & the final result. (Open question: is code sensitive to initial conditions?)

3. Make it Pass

Now that you have a failing test, change the system so the test passes.

Mistake: delete assertions so the test pretends to pass. Make it pass for real.

Mistake: copying actual, computed values & pasting them into the expected values of the test. That defeats double checking, which creates much of the validation value of TDD.

Mistake: mixing refactoring into making the test pass. Again with the “wearing two hats” problem. Make it run, then make it right. Your brain will (eventually) thank you.

If in the process of going red to green you discover the need for a new test, add it to the Test List. If that test invalidates the work you’ve done already (“Oh, no, there’s no way to handle the case of an empty folder.”), you need to decide whether to push on or start over (protip: start over but pick a different order to implement the tests). When the test passes, mark it off the list.

4. Optionally Refactor

Now you get to make implementation design decisions.

Mistake: refactoring further than necessary for this session. It feels good to tidy stuff up. It can feel scary to face the next test, especially if it’s one you don’t know how to get to pass (I’m stuck on this on a side project right now).

Mistake: abstracting too soon. Duplication is a hint, not a command.

5. Until the Test List is Empty, Go To 2.

Keep testing & coding until your fear for the behavior of the code has been transmuted into boredom.

I draw a flowchart from the article. Hope you like it.

https://whimsical.com/cannon-tdd-M74C15bNBdVmxhkLztnSXa

Good piece, thanks.

Order of tests: I recently did again the 'wardrobe kata' (https://kata-log.rocks/configure-wardrobe-kata) and there I found that there are two dimensions one can go in TDD-ing it: number of elements needed to fill the wall and number of different elements available. Both lead to completely different implementations for me.

There is also an uncle bob blog entry (in a weird comic style) where he explores order of tests and how it impacts code (once the resulting algorithm is bubble sort, once it's quick sort): https://blog.cleancoder.com/uncle-bob/2013/05/27/TransformationPriorityAndSorting.html

Very, very, interesting topic.